Economist

October 3, 2019

The airport at Hellinikon, a few miles south of Athens, closed in 2001. Planes belonging to Greece’s now-defunct national carrier still litter the runway. Nearby a stadium built for the Olympics in 2004 gently crumbles. In the distance, a marina borders the glistening Aegean. In 2011, when Greece was in the throes of a sovereign-debt crisis, the government put the site, which is three times as large as Monaco, up for sale. In 2014 it was snapped up by a consortium that planned to build homes, hotels and a casino. At an expected cost of some €8bn ($8.7bn), it was Greece’s largest investment project.

Five years on, ground has yet to be broken. When Syriza, a left-wing party, formed the government in 2015, it reopened the terms of the sale. Ambivalent ministers held up licences. The authorities demanded numerous archaeological surveys. Locals sued. Apart from boats docking in the marina and the occasional security guard on patrol, the site now lies desolate.

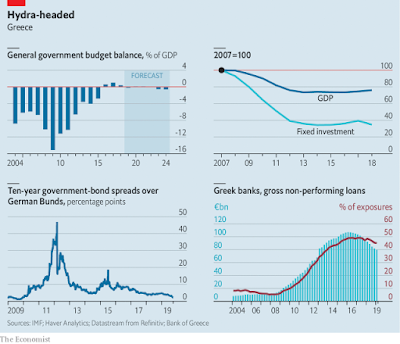

Officials from the imf and European Union who flew into Athens’s new airport in September are thus not short of examples of the difficulties of doing business in Greece. When the sovereign-debt crisis struck they bailed the country out on condition that it enact deep fiscal cuts and far-reaching regulatory reforms. Last year the eu struck a debt-relief deal, allowing Greece to exit its third and final bail-out, despite a public-debt burden of 180% of gdp. It required Greece to continue with reforms while hitting eye-watering targets for the primary-budget surplus (that is, before interest payments) of 3.5% until 2022, and then 2.2%, on average, all the way to 2060. In return it offered some interest-rate relief and extended the maturity of some loans.